Leadville, Colorado , 2019-Present

Award, 69th Annual Progressive Architecture Awards

“The idea was to give each person their own room—instead of the usual distribution—and to do most of the cooking right on the table—making it more a social campfire affair”

-R. Schindler

“…the _____ House comes disturbingly near to being a totally new beginning”

-R. Banham

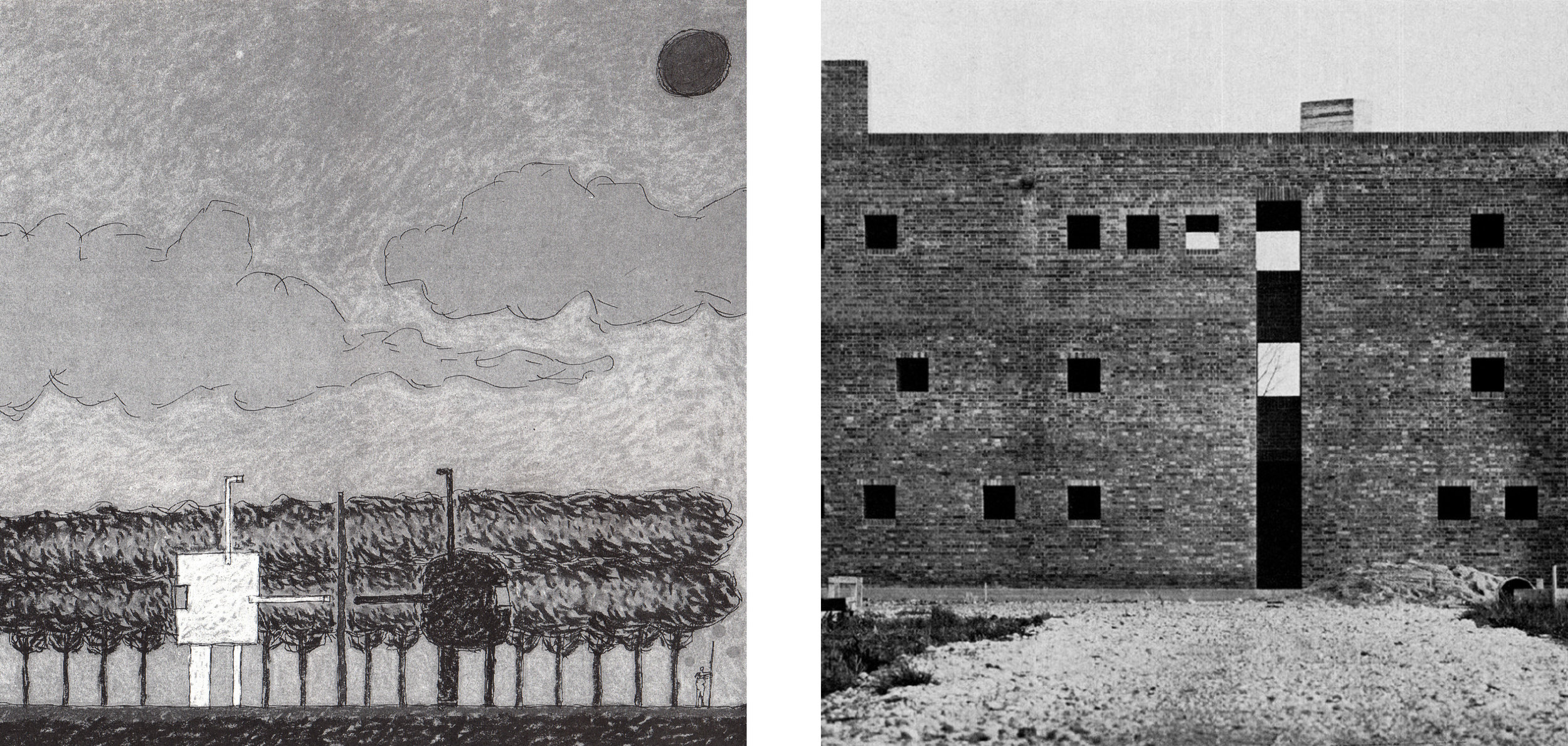

Table Cabin is a lean and discrete form of primitive domesticity. The cabin is conceived for a site without water rights or access to utilities. Built on the typology of the settler’s cabin, it is a campground whose prime viable assets are its isolation from the outside world and its access to viewsheds in the surrounding mountain valley. As such, Table Cabin is a warm repose separated from the world around it. A simple shelter constructed from conventional and readily accessible materials out of expedience and in search of novelty.

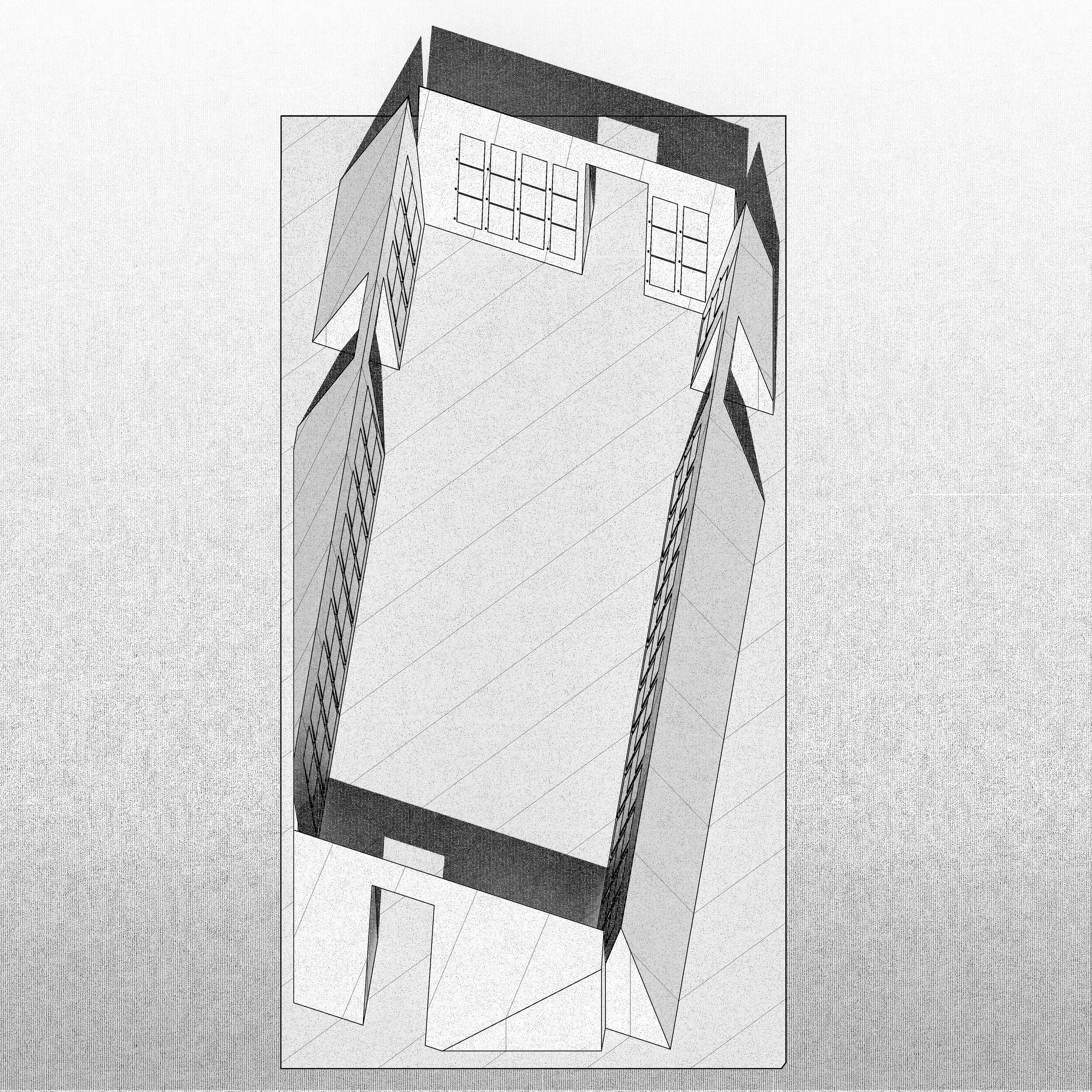

The cabin is a double-height wood-framed enfilade of living and dining spaces linked into an eight-foot wide corridor. The six-room linear configuration of the main level of the domestic structure allows for scaled privacy with sliding doors at each interior threshold.

Above the level of the door head in each room, nets are strung into the attic creating lofted sleeping quarters above. By leveraging this ample ceiling height, the house borrows a second floor without formally structuring it. The nets are accessed by hanging ladder and provide ample private sleeping space separated by the walls of each room. Access to the main house occurs at each room with an array of 14 doors distributed across the building façade in an even meter. These doors take over the role of the window, allowing for the elimination of conventional glazing. At times when the house is completely shuttered, daylight is gained through the insulated translucent polycarbonate roof.

The cabin is constructed utilizing an inventive approach to framing that utilizes stacked plywood for framing plates as an in-process evolution of simple conventional practices in platform frame construction that projects a clear direction forward in addressing vernacular American construction means and methods. The cabin will be constructed using 70% sourcing of lumber through offcuts of 2x4 and 2x6 lumber purchased through a recycling and salvage yard in Denver. Sorted into lengths ranging from two to four feet, the diminutive lumber sizing requires that the structure be built up into a series of framed platforms rather than a single conventionally built wall assembly. Each framing level is seated on a sandwich of four sheets of 1/2” OSB milled in a correlating stepped geometry. The apparent innovation in the project lies not in its use of lumber, but rather the use of conventional flatbed CNC milling in a simple and fast way to ensure precision and cost control for an otherwise highly articulated geometry.

By fitting the CNC workflow to tools commonly found in cabinet and carpentry shops around the Denver area, the production process can be easily replicated in future uses with minimal customization. The stacked plywood plates at each “level” are milled off-site to ensure accuracy without field measurement of the articulated geometry of the wall layouts. This mid-rise-in-miniature method of framing allows for the elevation to be developed into a single tapered mass without the need for field measurement. This out-of-scale articulation of levels lends itself to some play with the scale of interior spaces. The cabin is a single mass tapering into the six individual rooms from bottom to top and expressed at the exterior.

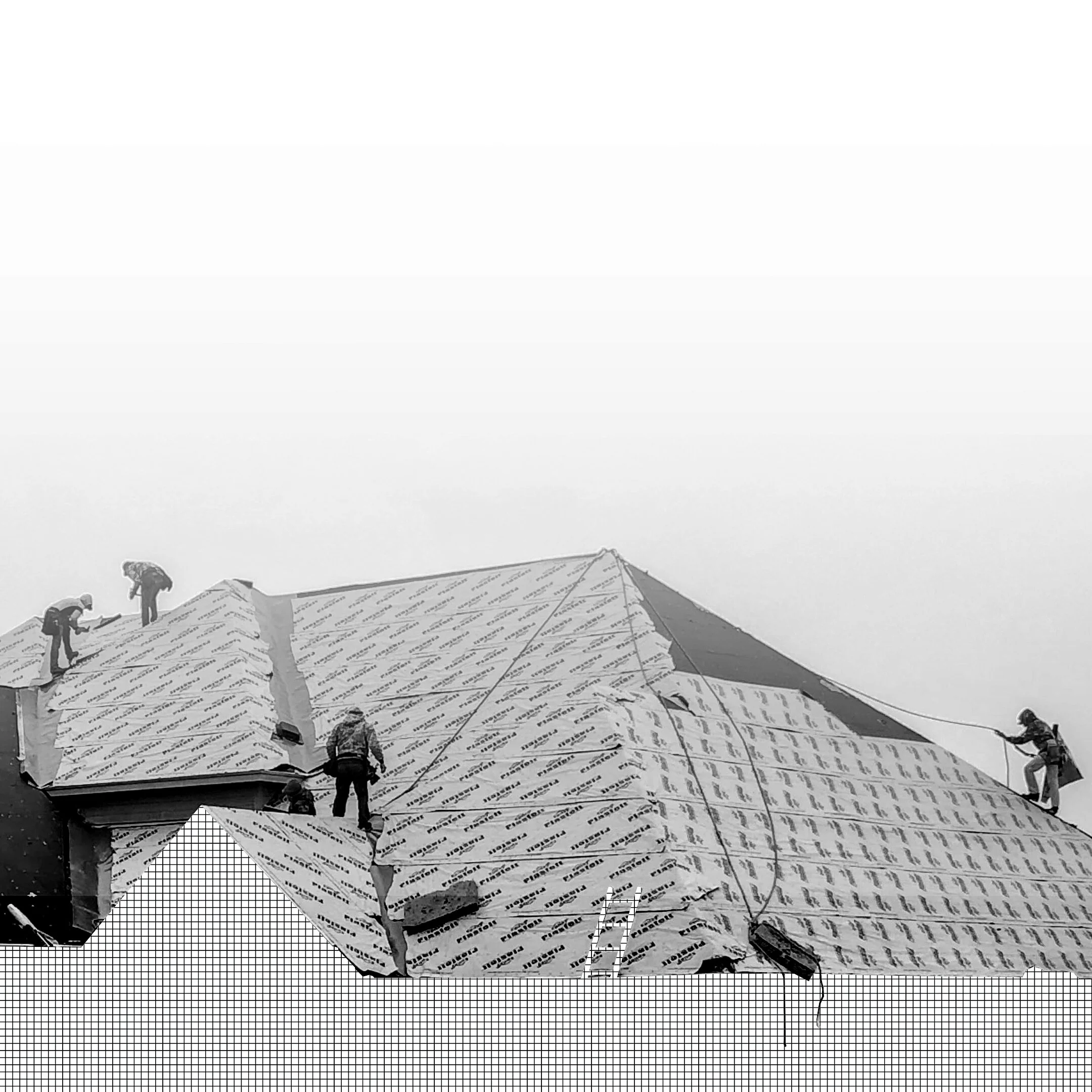

The structure is clad in a bituminous asphalt roofing membrane. By lapping the roof membrane up the building using a three-foot wide sheet of material, a meter begins to develop in dialogue with the structure. A simple linear pattern is roughly drawn onto the roof membrane as it laps up the façade, generating a disjunction between the legibility of the object and the staggered steps of its assembly. The use of a common sheet-applied roofing material is common in regional vernacular cabins from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The “tar paper shack,” the cheapest manifestation of the log cabin, was seen as the most cost efficient and expedient construction typology from this period, and the mountain region is still littered with their dilapidated remains. A byproduct of this lost typology remains today in the Colorado region, where roofing materials can be commonly found applied to facades in abundance, particularly in the Denver area’s prolific “Neo-Mansard” style structures of the mid-twentieth century. The roofing material provides a fast and low-cost solution to the envelope that ensures water-tightness without the need for miscellaneous metal flashing.

A scrappy and minimal dwelling, Table Cabin takes on the barest form of structured domesticity to provide a private second home for the two families who commissioned it. Not intended to be occupied year-round, it is a fixed campsite away from the urban bustle of Denver and the increasingly congested campsites of the mountain communities of Colorado. The reduction of complication that the cabin provides is a relief from the increasing connectedness and concern of contemporary life. Representing a return to primitive adjacency to the remote outdoors, Table Cabin provides a new form to a long-established rural typology.